The 2024 safety recall of many Bendix EC80 brake controllers has confirmed that there are safety implications of J2497 message reception. This blog post delves into the details of the recall, exploring the technical aspects, potential vulnerabilities, and the broader implications for fleet safety. We’ll examine the recall by considering the safety impact of J2497 vulnerabilities and the potential for malicious exploitation.

The Recall in Brief

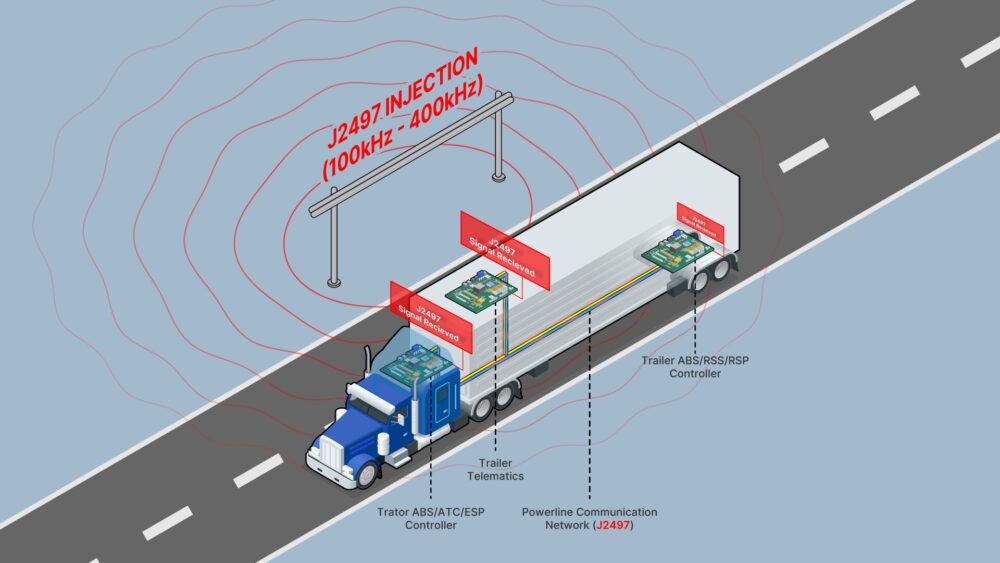

The recall, initiated by Bendix [1], involves a defect in the EC80 brake controller’s software that can lead to faults and crashes in the EC80 firmware, which could potentially affect braking performance. The recall cites “incorrect signal processing” as a cause (where the signal in question is the J2497 powerline (PLC) signal). The recall was triggered, in part, by a competitor’s technical service bulletin [1]. After the Bendix recall was published, all the affected OEMs: Volvo, International, and Paccar; subsequently issued their own recalls to address the affected units in their vehicles. This is the first case, to our knowledge, of confirmation of J2497 reception leading to safety impacts and has important implications due to CVE-2022-26131 (J2497 is wirelessly ‘writable’).

Pictured above: A graphic depiction of the wireless reception of J2497 signal on a tractor-trailer.

Technical Details and the “Competitor Technical Service Bulletin”

The root cause of the problem, as identified in the Paccar National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) recall document [5], is the incorrect processing of PLC by the EC80. This can lead to issues such as the ECU going offline and memory overwrites, potentially caused by incorrect message string length and overflow of memory buffers. When these sequences are received under conditions of high electrical noise and low PLC signal strength, they can trigger a fault, potentially causing a crash of the EC80 system. This is particularly concerning in trucks towing multiple trailers or using third-party trailer tracking systems, which can exacerbate signal degradation—as stated in the Bendix “24E086 Chronology” document [1], the issue is exacerbated by “high electrical noise and low Power Line Carrier (PLC) signal strength,” and “trucks towing multiple trailers (e.g. double and triple trailers) were more likely to exhibit the combination of high levels of electrical noise and low PLC signal strength.”

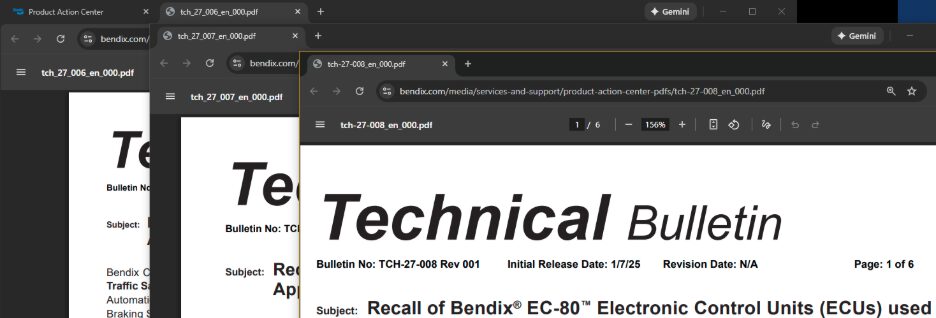

Bendix’s “24E086 Chronology” document [1] mentions a competitor’s technical service bulletin as a contributing factor in identifying the issue. While the exact bulletin remains undisclosed, analysis of publicly available TSBs suggests a cluster of communications from WABCO/ZF related to ABS signal integrity and noise as potential candidates, including bulletins like [2], [3], and [4]. This highlights that other ABS suppliers have had issues with processing J2497 signals in the past; in this case leading to excessive faults but never any safety impacts.

- Digging through the NHTSA TSBs archive was not straightforward using their online interface and rather than rely on third-party sites for our queries we cooked up some PowerShell to query and post-process them, see the appendix.

Inconsistent Descriptions and Missing Information

Intriguingly, the NHTSA recall reports from different OEMs offer varying descriptions of the cause. While Paccar’s report [5] points to “incorrect processing of PLC messages” and “memory overwrite effects,” International’s report [6] omits the cause entirely, and Volvo’s [7] cites “inadequate systems validation.” The Paccar NHTSA recall report, being the most recent, likely contains the most up-to-date information, suggesting that “memory overwrite effects” are indeed a key factor. Furthermore, the Paccar tech bulletin by Bendix [10] was released at a later date than those for International [8] and Volvo [9], which illustrates the evolving nature of the recall.1

Pictured above: Screenshots of the technical service bulletins for the three OEMs impacted.

- The initial release dates reported on the technical bulletins are in Nov 2024 for International and Volvo tech bulletins. Both were available on the Bendix Product Action website no later than Jan 2025 when we first visited it. However, the initial release date of the Paccar tech bulletin is “Jan 7 2025” in the PDF but this does not match its availability on the Bendix website. This tech bulletin was not available as late as March 2025 – but presumably had been shared to vehicle owners directly before it appeared on the Bendix website sometime after Mar 2025 and before Jun 2025.

The Safety and Security Implications

The recall is undoubtedly a safety-critical issue: it is a NHTSA-reported safety recall which triggered a firmware update campaign executed by a large proportion of owners over the course of 2025. According to the Bendix 24E086 Chronology document [1], the defect “may affect the performance of the electronic stability control (ESC) and/or antilock braking system (ABS) on the truck tractor and/or the towed vehicle,” while the Volvo NHTSA recall [7] states that “the braking performance of the combination vehicle may be affected,” and the Paccar NHTSA recall [5] notes that the defect can lead to the “ECU going offline,” which could indirectly impact braking. We did confirm with fleet safety personnel that it is absolutely a safety concern because the truck could malfunction in 1 of 2 ways due to the issue: suddenly stop, or not stop even if the brakes are applied”. In our experience the Anti-lock Braking Systems (ABS) on heavy vehicles are designed to fail-safe and the possibility of not stop[ping] even if the brakes are applied” seems very remote; we expect that the results of the ABS ECU going offline would include loss of speedometer, several warning lamps, a limp mode caused by this loss and warnings and a also a loss of the anti-lock functionality of the braking system. All of which are also significant enough to warrant a safety recall but it also should warrant commensurate concern about triggering this by malicious actors wirelessly as well.

This recall highlights the broader safety and security implications of vulnerabilities in the J2497 protocol, which, as demonstrated by CVE-2022-26131, is susceptible to wireless attacks. At the time of disclosure of CVE-2022-26131, our assessment was that any safety impacts by way of this vulnerability were highly unlikely, an opinion shared with us from other industry experts. Now, due to this recall, since random noise on J2497 is sufficient to have a safety impact, the ability to inject malicious messages wirelessly into the J2497 network now clearly could have safety impacts, particularly for vulnerable vehicles like road trains and tankers.

Memory Corruption and Remote Code Execution

The Paccar report’s [5] mention of “memory overwrite effects” suggests the possibility of a memory corruption bug. Such bugs can have far-reaching implications, potentially leading to remote code execution (RCE). If the EC80 firmware is indeed vulnerable to memory corruption, attackers may be able exploit this, depending on the details of the corruption, to gain control of the brake controller, potentially turning units into “sleepers” awaiting commands, permanently bricking them, or using them as a stepping stone for further ingress into vehicle networks (e.g. J1939). This is a theoretical impact beyond the clear safety impacts that already drove the need for timely patching and remediation.

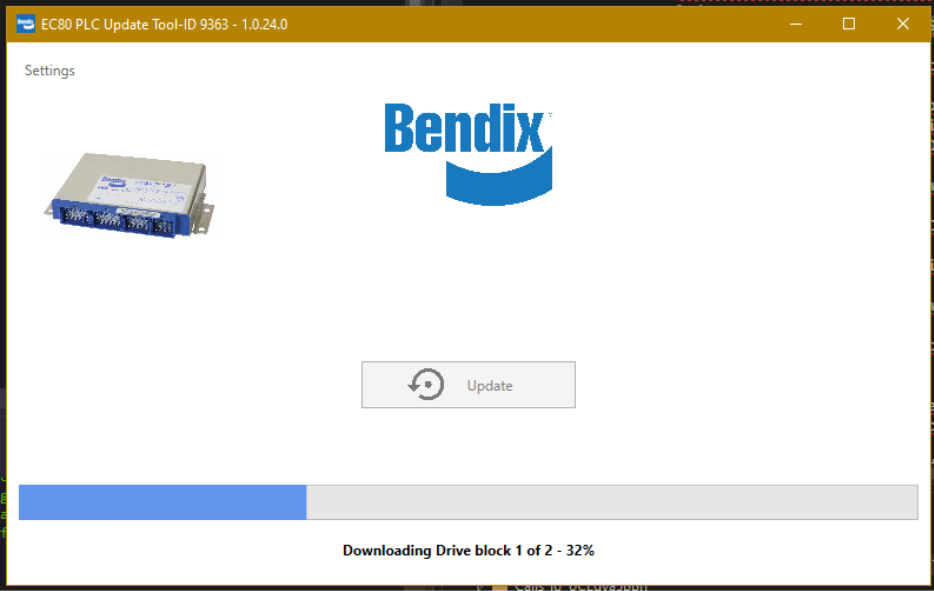

To address this critical safety issue, Bendix has released a standalone .NET software update utility known as “ID 9363”. It corrects the defect by updating the firmware of affected EC80 controllers. This same utility is used across all OEMs as indicated in their respective technical bulletins [8] [9] [10]. While we have observed the firmware update process multiple times using this tool, we have no specific findings to share publicly at this time. Further investigation and analysis of the update process and its implications are ongoing. Given that the update process is executed on fleet maintenance laptops and in a high volume of affected units we feel this is an important follow-on aspect to thoroughly investigate for security of our fleets and of the industry.

Pictured above: A screenshot of the ID 9363 utility (v1.0.24.0) in action.

Conclusion

The potential for J2497 vulnerabilities to be exploited, coupled with the possibility of memory corruption causing the ECU to go offline and potentially also leading to RCE, demands a proactive approach to security. Mitigating these risks, particularly on vulnerable equipment like road trains and tankers, is paramount. This recall should remind the industry that improved testing, and a stronger focus on cybersecurity within the commercial vehicle sector is necessary for this wirelessly accessible heavy vehicle segment. The industry must prioritize the development and implementation of robust security measures to protect against future attacks and ensure the safety of our roads.

The convergence of potential J2497 exploits, memory corruption vulnerabilities, and the possibility of malicious actors gaining control of critical vehicle systems creates a complex and concerning threat landscape. Addressing these challenges requires a concerted effort from all stakeholders to enhance security practices and safeguard the integrity of commercial vehicle networks.

The NMFTA is currently participating in Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) T&B meetings where we are advocating for a next version of J2497 standard document which highlights the security risks and recommends: 1) move all software functions (other than trailer ABS fault lamp) off of J2497 in future tractor-trailer interfaces and 2) deploy mitigations on new tractors to protect legacy trailers.

References

[1] Bendix “24E086 Chronology” Document: https://static.nhtsa.gov/odi/rcl/2024/RMISC-24E086-5355.pdf

[2] TSB 10194446: https://dot.report/bulletins/10194446

[3] TSB 10176745: https://dot.report/bulletins/10176745

[4] TSB 10222229: https://dot.report/bulletins/10222229

[5] Paccar NHTSA Recall: https://static.nhtsa.gov/odi/rcl/2024/RCLRPT-24V915-6438.PDF

[6] International NHTSA Recall: https://static.nhtsa.gov/odi/rcl/2024/RCLRPT-24V818-4283.PDF

[7] Volvo NHTSA Recall: https://static.nhtsa.gov/odi/rcl/2024/RCLRPT-24V790-3386.PDF

[8] Volvo Technical Bulletin: https://www.bendix.com/media/services-and-support/product-action-center-pdfs/tch_27_007_en_000.pdf

[9] International Technical Bulletin: https://www.bendix.com/media/services-and-support/product-action-center-pdfs/tch_27_006_en_000.pdf

[10] Paccar Technical Bulletin: https://www.bendix.com/media/services-and-support/product-action-center-pdfs/tch-27-008_en_000.pdf

Appendix: Parsing TSBs from NHTSA with PowerShell

Getting useful answers out of the TSBs stored by NHTSA is not straightforward. The other repositories hosted by NHTSA have better structure and indexes but for the NHTSA Communications archive of TSBs e.g. https://static.nhtsa.gov/odi/ffdd/tsbs/TSBS_RECEIVED_2020-2024.zip you are on your own.

Here’s some example PowerShell commands that might help you find stuff in there:

Limit the 4-year TSBs block to just one year (here 2024):

Get-Content .\TSBS_RECEIVED_2020-2024.txt | sls 2024 | Set-Content -Path .\TSBS_RECEIVED_2024.txt

For the next few, save the headers of the 4-year block to .\TSBS_RECEIVED_headers.txt so that tables can be made.

Generate a table of the TSBs matching some terms (here ‘sls’ and ‘wabco’):

$(Get-Content .\TSBS_RECEIVED_headers.txt; Get-Content .\TSBS_RECEIVED_2023.txt | sls wabco) | ConvertFrom-Csv -Delimiter “`t” | Format-Table -auto *

Generate a table of TSBs NOT matching “VAN HOOL”, “AUDI” et al (to remove passcar hits) and also matching some terms (here ‘service brakes, air’):

$(Get-Content .\TSBS_RECEIVED_headers.txt; Get-Content .\TSBS_RECEIVED_2020-2024.txt | sls -Pattern @( “VAN HOOL”, “AUDI”, “CADILLAC”, “FORD”, “LINCOLN”, “JEEP”, “ISUZU”, “GENESIS” ) -NotMatch | sls “service brakes, air”) | ConvertFrom-Csv -Delimiter “`t” | Format-Table -auto *

Generate a table of TSBs matching some common HD OEMs and also matching some terms (here ‘service brakes, air’):

$(Get-Content .\TSBS_RECEIVED_headers.txt; Get-Content .\TSBS_RECEIVED_2020-2024.txt | sls -Pattern @( “FREIGHTLINER”, “HINO”, “WABCO”, “HALDEX”, “DAIMLER”) | sls “service brakes, air”) | ConvertFrom-Csv -Delimiter “`t” | Format-Table -auto *